By Jodi Boone

Part One of a new series of articles on important yoga luminaries introduces the Hindu sage Patanjali who codified the oral tradition of yoga into a concise written form in a series of sacred texts known as the Yoga Sutras. Jodi introduces us to this mythical character and these important texts which are the foundation of yoga philosophy and required reading for all serious yoga seekers.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras outline a path for obtaining divine oneness, self-realisation or, as Nicolai Bachman says in his book The Path of the Yoga Sutras, a deep understanding of the core of who you are. Among yogis and spiritual seekers, this promise is very inviting. What is even more attractive is that the path is laid out in 195 short verses (or 196, depending on the school of thought). You could easily read the entire Yoga Sutras in 30 minutes or less. However, making sense of these pithy lines is a different, and much longer, story. Like yoga, studying the Sutras could span a lifetime. There are dozens of translations of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, and they vary because the terse verses leave much room for interpretation.

The name Patanjali means “falling from joined hands” (in Sanskrit, the word patat means falling and anjali means joined hands). As with most great Indian mystics, sages and priests, there are mythical stories explaining their incarnation (or reincarnation). The myth widely held for Patanjali is that he deeply desired to share with the world the teachings of yoga and other knowledge so he chose to be reborn as a seven-year-old boy, falling from the ethereal world directly into his mother’s hands, a Brahmin woman named Gonika. For this reason she named him Patanjali (Source: David Gordon White’s book, The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography).

Although no one is certain, scholars believe Patanjali lived sometime between 500 BC and 200 AD. Patanjali is not only credited with writing the Yoga Sutras, but also works on ayurveda and Sanskrit grammar. Because of his prolificacy, some scholars question whether Patanjali was one person or if the name refers to a collective group of sages and teachers. Where everyone is in agreement though is that Patanjali brilliantly codified the vast oral tradition of yoga into a concise written form. He did not develop yoga, this science existed thousands of years before Patanjali.

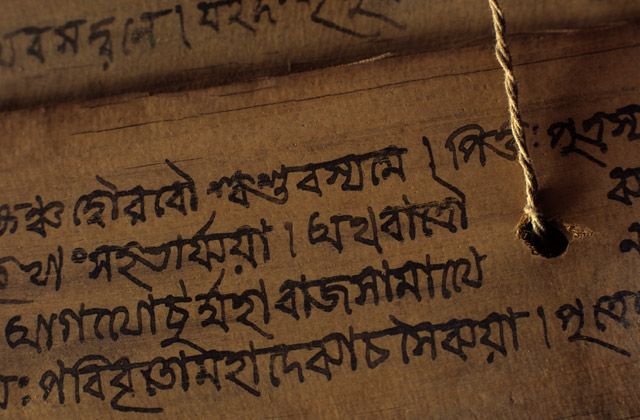

In India, the ancient tradition of orally transmitting knowledge through the chanting of mnemonic verses is still practiced today, helping students recall knowledge passed down from their teachers. In Sanskrit, the word sutra means thread, and each densely packed and succinctly written Sutra represents a large amount of knowledge. Chanting the verses helps students with memorisation and pronunciation. The belief is that students are not ready to question their understanding of a teaching until they have committed the knowledge to memory and mastered the pronunciation.

The inspiration of the Yoga Sutras comes from the Vedas, which are the most ancient Hindu texts in India, as well as the foundation of Hindu spirituality. Today, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras remain the primary text on yoga philosophy. The first verse of the Yoga Sutras is translated as: “Now the teachings of yoga.” Today, a reader may assume that Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are about asanas, or postures, which is the modern day connotation of yoga. Although, after reading just a few lines, it is clear that Patanjali is concerned with meditation and ultimately, self-realisation. The text says very little about asana. What is shared about asana relates to finding a comfortable sitting position for meditation.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are divided into four chapters, or Padas:

1) Meditative Absorption

2) Practice

3) Mystic Powers

4) Absolute Independence

The Sutras explain the nature of reality, our misunderstanding of the nature of reality and the practices necessary to see reality clearly. As Chip Hartranft says in his book, The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali, “Though brief, the Yoga Sutras manage to cut to the heart of the human dilemma.”

The main problem, Patanjali says in his Sutras, is a misunderstanding about consciousness and ’pure awareness’. They are separate, but are often perceived by humans to be one and the same. Patanjali’s solution for this is to allow consciousness to settle from the whirling thoughts, sensations and emotions to a point where it can reflect ‘pure awareness’ back to itself. This is addressed right away, in the second verse: “Yoga is to still the patterning of consciousness.“ When this is achieved, we connect with our source of true happiness – pure awareness. The path Patanjali lays out is a journey within, accessible to anyone, offering deep, universal insight that guides practitioners to freedom.

Today, the philosophy from the Sutras that yoga practitioners are most familiar with is The Eightfold Path, or Ashtanga Yoga (unrelated to the asana system founded by Pattabhi Jois), which appears in Chapter 2, Verses 28 – 32. Ancient lore says that when a student approached a teacher to study yoga, the teacher would require him to master the yamas and niyamas, the first two limbs of the Eightfold Path, before returning to learn asana.

With the many translations of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras available today, deciding on which one to read may feel overwhelming. In choosing a translation, you could approach this similarly to finding a yoga teacher – someone you resonate with and enjoy spending “time” with – Edwin F. Bryant’s translation is 598 pages long with an 8-point font!

Like Ayurveda, yoga’s sister science, yoga was given to humanity as a gift. Ayurvedic philosophy is focused on longevity and leading a life of well-being. In the case of yoga, the practices are dedicated to ending the ‘mundane’ cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Ultimately, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras speak to the greatest desire of every human being – how to end the cause of suffering and find eternal happiness.

Look out for our next article which will examine the 1st limb of Patanjali’s Eightfold Path.

Photographs by Coni Hörler.

Yoga in true sense the ultimate in life.

thank you for the enlighting infomation , interesting reading.